‘Backyard Boat’ Being Restored Is a SoCal Treasure

Byline: Taylor Hill

NEWPORT BEACH — As the latest chapter in shipwright Dennis Holland’s years-long backyard boatbuilding odyssey unfolds, the dichotomy between Newport Beach’s crackdown on residential construction projects and boaters’ interest in saving an icon of California’s sailing history has never seemed more apparent.

To the city of Newport Beach, the 72-foot wooden sailboat named Shawnee is a problem. The large vessel has been kept in the side yard of Holland’s Newport Beach residence along Holiday Road since 2006, with the bow jutting out toward the street, and the stern sitting inches from a wall overlooking a neighbor’s backyard pool.

While Holland’s Shawnee restoration project was originally approved and permitted by the city, new Newport Beach City Council members, a new city manager and new neighbor’s complaints have seemingly spelled doom for the historic wooden vessel, leading the city to create an ordinance in 2009 banning long-term large construction projects on residential land.

When Holland insisted that the city stick to its original agreement to permit the project, hoping to be grandfathered into the new rule, the city moved to sue Holland in June 2011. Superior Court Judge Gregory Munoz issued a preliminary injunction March 1, giving Holland until April 30 to remove the boat from the yard.

Councilman Rush Hill, whose district includes Holland’s home, said that time is up for Holland, and that the issues at hand aren’t about the boat, but conducting an industrial function in a residential area.

But to Cyndi Adler, whose family grew up with Shawnee, the only thing that matters is the boat.

(For more photos of Shawnee, click here )

“That’s one thing that has really bothered me about this story,” Adler said, referring to the media coverage on the boat’s uncertain future. “People are comparing Shawnee to an old car or an RV in someone’s backyard. But she is so much more than that. She’s a California treasure, and we’re not treating her like it.”

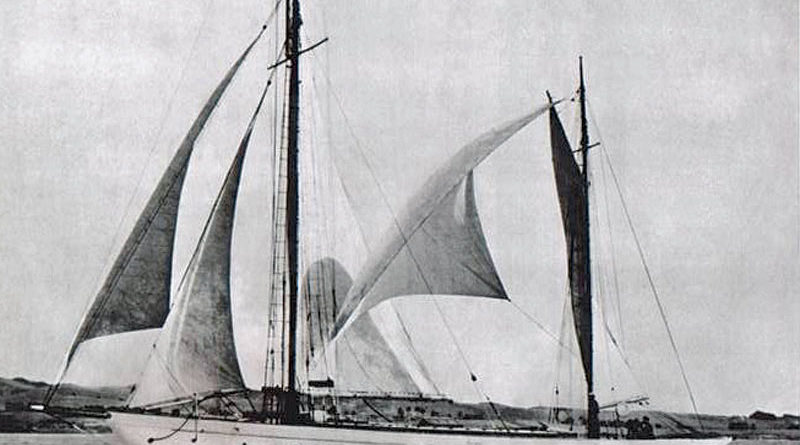

Constructed in 1916 on the East Coast at a Boston boatyard, Shawnee was built as a wedding present for Mark Fontana, one of the founders of Bank of America, whose family the California city was named after.

Designed by shipwright Arthur Benny, Shawnee offered a remarkably spacious hull design for a boat of its size, while maintaining keen sailing lines and an effortless elegance.

The honeymoon yacht made its way aboard a freighter through the Panama Canal — one of the first ships to do so — and then headed north to San Francisco Bay.

Shawnee became the flagship of St. Francis Yacht Club, competing in the first-ever Transpacific Yacht Race to Tahiti in 1925, taking third place in the event.

After changing hands among a few owners during her time in San Francisco, Shawnee became the property of the Navy during World War II, serving as a patrol vessel searching for enemy craft off the California coast.

After the war, the vessel fell into disrepair, just as Cindy’s mother and father – Rebecca and Allan Adler — became interested in buying a boat.

Allan Adler had begun to make a name for himself in Southern California as a world-renowned silversmith, whose sleek designs in sterling silver became sought after from coast to coast. Adler learned Shawnee was for sale, and in 1954, after putting in some solid repairs and renovations, he brought the vessel down to Newport Harbor.

Over the next several decades, Shawnee’s home remained Newport Harbor, and her mooring was located directly across from Newport Harbor Yacht Club.

But, according to Cyndi, the boat didn’t stay in one place very long. The family was always out on excursions to Catalina, daysailing up and down the California coastline and taking extended cruises to Canada and Mexico.

With Allan Adler’s career as “Silversmith to the Stars,” many Hollywood celebrities and motion picture industry executives enjoyed time aboard Shawnee, taking trips with the family across the channel to Catalina — and always becoming part of the crew.

“When people came aboard for a sail, it wasn’t the typical yachting experience, where captains would sail and crewmembers waited on you hand and foot,” Cyndi said. “You worked — grabbing the line or taking out the sail. And everybody came away from her saying it was the experience of a lifetime.”

That experience is one Adler is concerned may be lost if Holland’s restoration of Shawnee is halted.

When she was first married, Cyndi spent two years living aboard Shawnee with her husband until their son was born — quality time on the vessel she said gave her an even deeper understanding of the boat’s historical significance.

“There’s a soul of a wooden boat that is just hard to explain unless you’ve been involved in wooden boats, and that’s why we’re so passionate about her,” Cyndi said.

“She’s just such a beautiful classical design,” Adler said. “Especially for a turn-of-the-century design. She was just so elegant, and had this extensive main salon and large stateroom, and with cut glass down below, a fireplace…she was just a beautiful yacht.

As the years went by, and Allan and Rebecca Adler grew older, Shawnee began to show her age, too. Following Allan Adler’s death in 2002, Shawnee was in need of extensive work if the boat was to be brought back up to its previous luster.

“None of us had the ability to keep her going like my dad had,” Cyndi said.

Before her father died, Cyndi said she had promised him that Shawnee would live on — a promise that led the family to a familiar face in the wooden boat-building community: Dennis Holland.

During the 1984 Summer Olympics, a tall ship parade was held in Long Beach, and the Adlers took Shawnee up to participate in the event. There, they got their first glimpse of Holland’s work: the newly completed 118-foot replica of the 1800s-era brig Pilgrim.

“We realized he was the only person on the West Coast that could rebuild Shawnee, and who had the passion to do so.” Little did the Adler family know that Holland had been eyeing Shawnee for years, originally catching a glimpse of the boat in a 1953 yachting magazine, sailing in the Tahiti Race.

“It wasn’t just her beauty I fell in love with, but her construction, too,” Holland said. Like Cyndi, he mentioned the boat’s cockpit layout, her medium-size transom and the boat’s tendency to feel “as if it’s breathing” when at anchor.

“She’s one of the most historic yachts on the West Coast,” Holland said. “Most yachts come in from other places, but she’s spent her life here.”

Holland’s backyard boat-building activities started at age 10, with his first project – an 18-foot Malibu — taking two years to complete. In 1958, at age 13, he launched the boat near his parent’s Long Beach residence and sailed to Newport Beach.

“That was my first view of Newport Harbor, on that boat,” Holland said. He spotted Shawnee on her mooring during the voyage, and decided to keep an eye on the boat from then on.

His family moved to Costa Mesa from Long Beach in 1959 — to get a bigger yard for his boats, Holland said.

Over the years, he always took note of Shawnee at its Newport Harbor YC mooring and on numerous trips to Catalina, admiring from afar the boat he had always felt close to.

“To me, it’s kind of a romantic thing, because of all of the history that’s wrapped up in her,” Holland said. “Sometimes when I would see her on a mooring at Catalina, I would put my rowing boat over the side and paddle up next to her, just watching as she’d slowly respond in a graceful motion to the water.”

Years later, Holland was crewing aboard Newport Beach residents Robert and Beth Millett’s 65-foot yawl Olinka when he noticed Shawnee at her mooring, low in the water, with sail covers flapping in the wind.

“I saw the condition she was in, and knew I had to call the owners,” Holland said. Two weeks after Allan Adler’s funeral, Holland spoke with Rebecca Adler, telling her he would act as the boat’s caretaker until an owner could be found.

Soon after, the Newport Beach Harbor Department and yacht club officials agreed to have the vessel removed and possibly sunk — a decision Holland said he could not live with.

“The Adlers had me guarantee that I would restore the boat, so I decided to take the project on,” Holland said.

On May 2, 2006, the city had Shawnee transferred from Newport Harbor to its current location at Holland’s side yard.

In its current state, the boat’s lead ballast keel remains separated from its ribs and planks, and multiple rusted screws, rotten beams and soft wood need to be removed before the boat can begin taking shape again.

More than five years into the project, Holland — who only works with family members on the boat — suspects another six years is needed for the project to reach completion. In comparison, Pilgrim took Holland 13 years to finish, and his original estimate was three.

At 67, Holland has been battling prostate cancer since 2006, which has slowed his progress on Shawnee. Many view the shipbuilding project as “Mr. Holland’s Opus,” — a final work by a composer with rare talent on an even rarer music sheet.

Whether or not Holland will be able to complete Shawnee remains a mystery, but the city’s current course of action could prevent him from getting that chance.

“To think of what Dennis has given to the nautical history of Orange County with building the Pilgrim and now restoring Shawnee, I just don’t see anybody else doing anything like this,” Cyndi Adler said. “Dennis isn’t asking for money; he just wants the city to leave him alone so he can finish it.”

As the April 30 deadline looms, Holland continues to work on Shawnee, all the while reminiscing on what made him go to such lengths to save the ship in the first place.

“In all of her design, I wouldn’t change a thing,” Holland said. But the question of whether the city will change its mind about the boat remains unanswered.